This homily on the 6th Sunday after Pentecost reflects on the Gospel account of the healing of the paralytic, revealing Christ’s power to heal not only the body but also the soul wounded by sin. Through the faith of the paralytic’s friends, the importance of intercessory prayer, and the revelation of Christ’s divinity, the sermon calls the faithful to repentance, love for neighbor, and participation in the divine grace that restores wholeness to the human person. At the center stands Christ—the God-Man, the Physician of souls and bodies—who, through His Church, invites us to live in fullness and to await the coming of the Kingdom of God.

Sixth Sunday After Pentecost

(Matthew 9:1-8)

Homily on the 6th Sunday after Pentecost – Healing of the paralytic

Today’s Gospel speaks of an event we also heard on the Second Sunday of Great Lent. On that day, the reading was from the Gospel according to St. Mark, chapter 2, verses 1–12, which gives a more detailed account of the healing of the paralytic. Since that Sunday is also the Sunday of Orthodoxy, homilies often focus on the Triumph of Orthodoxy rather than on this Gospel passage. Therefore, this repetition—though in a shorter version—of the Gospel concerning the healing of the paralytic affords us an opportunity to reflect on this great miracle of Christ, a healing not only of the body but also of the soul, wounded by sin.

The Holy Evangelist Mark emphasizes that the friends of the paralytic brought him before Christ by lowering him through an opening in the roof of the house, so that he might be healed by Him. They had encountered an obstacle before the house where Christ was present: because of the great crowd, they could not reach Him. How often do we too encounter obstacles that convince us there is no solution, that deliverance from our afflictions is impossible? Yet, a way forward always exists.

Because they could not enter the house due to the crowd, they climbed the outer steps to the flat roof, removed the beams and straw, and lowered the sick man before Christ. This action serves as a lesson for us, that we must rise above obstacles and distractions. When we lift ourselves up in prayer before the throne of God, those obstacles remain below us. This is why, in the Divine Liturgy, we are exhorted to “Lift up your hearts.” As the Psalmist says: “I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help. My help cometh from the Lord, who made heaven and earth” (Psalm 121:1–2).

In doing this, the friends of the paralytic showed that they cared for him deeply, that they were willing to do anything to bring him healing, and that they believed in the power of Christ. In a particular way, Christ here teaches us about the power and importance of intercessory prayer. The paralytic was entirely dependent upon others. Although the Gospel does not state that they verbally requested healing from Christ, His response allows us to presume as much. We note that Christ perceives their faith—namely, the faith of the four friends—not the faith of the paralytic himself. Christ has, in other instances, praised the personal faith of those He healed. To the blind man, to whom He restored sight, He said: “Thy faith hath saved thee” (Luke 18:42). He commended the faith of the Canaanite woman (Matthew 15:28). But here the Lord looks upon the faith of those who brought the paralytic to Him. This does not mean that the paralytic himself had no faith—faith was likely all that remained to him after all other hope had failed—but the faith of his friends is what is here emphasized. They offered concrete help and prayed for his healing.

Christ also teaches us here about the love of neighbor, especially toward those who are in some way dependent upon us. How willing are we to support others through prayer? It is the will of God that we pray for one another and thereby bear witness to mutual love. When someone is sick, the Apostle James instructs that the elders of the Church should be summoned to pray over the one who is ill. Such prayer, he says, offered in faith, shall save the sick, and their sins shall be forgiven (James 5:15). James further affirms that not only presbyters (priests), but all Christians are called to intercede for one another: “Pray one for another, that ye may be healed” (James 5:16). It is not enough to pray; we must also render concrete help to those in need. The paralytic had four friends without whom he could not have come to Christ. Are we present for our neighbor when, for instance, they need a priest for prayer but are themselves unable to reach him? Or for those who are not able to come to church, could we offer to bring them? There are many ways in which we, too, may be people of faith on behalf of others.

Unlike St. Mark’s Gospel, which gives a fuller account of this event, St. Matthew places the emphasis on the forgiveness of sins. Christ does not say to the paralytic, “Be healed,” but rather: “Thy sins be forgiven thee.”

Sin is a far graver paralysis than any bodily affliction. Sin separates us from communion with God; it disfigures the divine image in which we were created; it deprives us of a life of dignity on earth and the life of glory in eternity. In the spiritual sense, as St. John of Kronstadt says, we are all paralyzed. Christ came to heal us from this spiritual paralysis.

The scribes—the guardians and interpreters of the Law—who were present, said in their hearts: “Why doth this man thus speak blasphemies? Who can forgive sins but God alone?” The forgiveness of sins belongs to God alone. By exercising this divine authority to forgive sins—both here and elsewhere—Christ clearly manifests His divinity. Through His deeds, Christ revealed Himself as God. And in this, the Jewish religious leaders perceived blasphemy. But Christ would reveal yet another divine attribute: He knows their thoughts. He makes it known to them that He is aware of what they think, and answers them, affirming that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins.

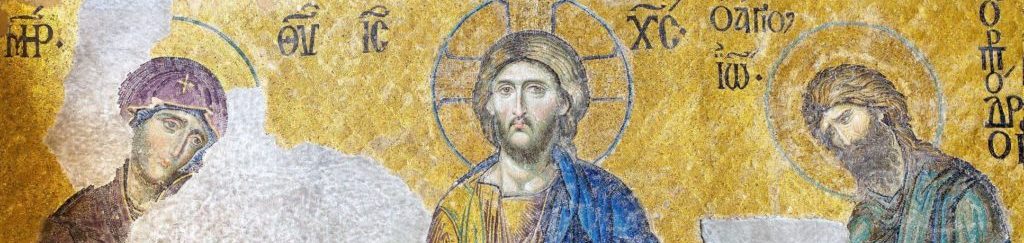

This is the first time Christ refers to Himself as the Son of Man. The evangelists refer to Him as Lord, Son of God, Son of David, and Savior, but the title “Son of Man” is used exclusively by Christ, and only of Himself. By using this name, Christ affirms that He is the Messiah and that He is, though divine by nature, also truly human. If He had been merely human, there would have been no need to emphasize His human nature—for that is presumed in every mortal. But precisely because He is more than man, Christ calls Himself the Son of Man. Christ is God who has become Emmanuel—God with us—in human flesh. He is both Son of God and Son of Man: the God-Man.

This title also places Christ within the context of the prophetic vision of the Prophet Daniel:

“I saw in the night visions, and, behold, one like the Son of Man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of Days, and they brought Him near before Him. And there was given Him dominion, and glory, and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve Him: His dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and His kingdom that which shall not be destroyed” (Daniel 7:13–14).

He, whose dominion is eternal and whose Kingdom is indestructible, declares to the scribes that He has the authority to forgive sins.

Christ, having forgiven the paralytic his sins, then heals him of his bodily affliction as well: “Arise, take up thy bed, and go unto thine house.” Christ gives precedence to the state of his soul, and only then heals his body. This is the third affirmation of His divinity in today’s Gospel. After forgiving sins and revealing the secrets of hearts, He confirms Himself as the One who has power to heal.

The word “healing” implies that something broken is made whole again. When Christ heals, He heals the entire person—soul, body, and spirit. The forgiveness of sins is a greater healing than physical restoration. We may die in perfect physical health, but if our soul is not healed, if our sins are not forgiven, if we have not reconciled with God through repentance, then we shall enter eternity without Christ. On the other hand, we may die suffering from severe illness, but if our sins are forgiven, if we are reconciled with God, if our soul is healed, then Christ awaits us in heavenly joy.

The reality is that the root of many physical and psychological afflictions in the modern age is the same as in the case of the paralytic—unrepented sin. And such sins remain unforgiven not because God is unwilling to forgive, but because many do not come before God in confession and ask forgiveness.

The healed man takes up his bed, as the Lord commanded him, and goes to his home. Until then, the bed had authority over him. After Christ healed him, he no longer depends on the bed—he takes it into his own hands. He governs the bed; the bed no longer governs him. When the Lord sets us free, it means we take control over those things that once enslaved us.

The healing of the paralytic evoked wonder and the glorification of God among those who witnessed it. Among them, through Christ, the Kingdom of God is made manifest. Christ was doing something new, something those present had never before experienced or seen. Do we recognize the hand of God in our own lives? Do we give thanks to Him for all that He does for us?

The Christ of today’s Gospel is our Lord and our God. Through repentance, the Lord heals us of our spiritual paralysis, of our sin. All that is broken within us, He is able and willing to restore and make whole. This healing is of greater value than any physical recovery. Then our life will have meaning and purpose. Then we may live the fullness of this earthly life in wholeness, and await the glory of the life to come in the Kingdom of God. May God help us in this. Amen.

Author: Jasmin Milić, PhD